A Dream of a Ridiculous Man

Dostoevsky uses this short story as an expression of his core rejection of ‘Reason’ as a basis for understanding the psychology the behavioural machinations and doings of humankind. The dominant ideological tide of the nineteenth century, driven by French philosophers and writers and British social scientists, was rationality, which was seen as the core force shaping human action.

‘Nonsense!’ was Dostoevsky’s retort. A retort most savagely expressed in the two parts of his ‘Notes from the Underground.’ In this part polemic, part illustrative exegesis, he sets about demolishing the very notion of ‘the rational human being’ calling down a plague upon the House of Reason. ‘ The Dream of a Ridiculous Man’ is short cursive and ironic take on the liberal ideal of man.

Dostoevsky’s anonymous everyman ‘the Ridiculous Man’ of course obeys logic but not reason. Given the concatenation of events and his own contrary nature the protagonist propels himself into a number of contradictory dilemmas before falling into a dream in which he finds and then destroys a society of perfect people, demolishing the pipe dreams of those political idealists whose ambitions are to build perfect societies based on a rational estimation of human kind.

Dostoevsky would have enjoyed the irony of Trump’s Presidency - you start with the vision of founding a New Jerusalem and end up with the tyranny of populist white supremacist.

Review by Peter Mortimer

Stream of consciousness writing has a lot to answer for. As an editor I’ve been inflicted with endless manuscripts of formless stodge, authors keen to offload their pseudo-philosophcal ramblings but without a proper story to tell.

Lawrence’s suggestion, "trust not the teller but the tale" remains good in most instances. Where does this leave Adrin Neatrour’s one-man adaptation and performance of the Dostoevsky story, in which, let’s face it, not a lot externally happens?

Well, I say that, but the main character does die, get buried alive, transported to another planet, corrupt that planet with human failings and conclude, as Auden puts it a century later, "we must love one another or die".

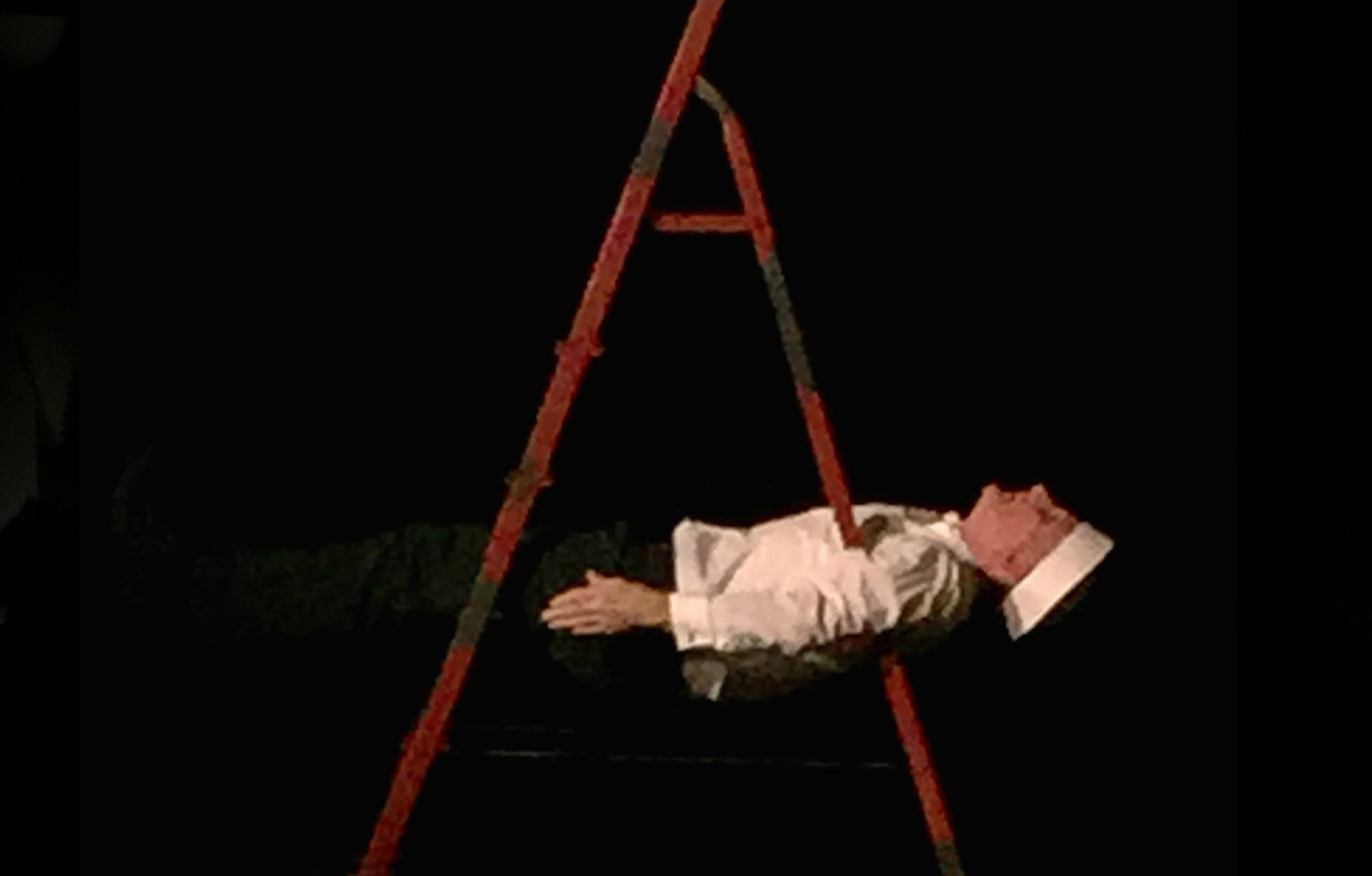

It’s mainly in the head though, y’see… Luckily Dostoevsky is not your average scribbler, nor is Adrin Neatrour your average luvvie. He likes tackling the heavyweights in his one-man shows, coming to this from his previous Kafka adaptation, bringing a kind of comic intensity, a style which merges the slapstick and the intellectual, his body contorting round a pair of stepladders or going into a series of spasmic jerks (Dostoevsky suffered from epilepsy) as he takes us through the tale of one man’s existential crisis.

The piece opens begins with William Blake’s short poem from Songs of Innocence and Experience, "The Sick Rose", a deceptively simple yet powerful evocation of flawed beauty and how possibly we are condemned to disappointment.

Our character is in an "existential abyss". His life he says is in "a state of non-existence". He stares nightly at his bedside gun and ponders ending it all. Except he fears that if he dies, the entire world may die with him.

These obsessive musings are interrupted in the street one day by a young girl who pleads with him to come to the aid of her dying mother. He does not, but the incident stays with him, regularly invading his obsessive thoughts about his own intellectual well-being.

Thus he embarks upon his dream. Dreams are normally bad news in books, plays and films and we often yearn for them to end. This too is a little flabby at the start though resonates later as we later as we realise humanity’s almost subconscious tendency to pollute and corrupt.

On a bare stage and with only the set of stepladders as a prop, Neatrour twists himself into all manner of metaphysical situations, each line delivered with a kind of wide-eyed curiosity at the absurdity of the world around him. The stylized movement is at times reminiscent of silent movies.

He reminds us constantly that he is an idiot which leads us to the inevitable conclusion that so are we all. Neatrour’s refusal to be at all po-faced about these mighty musings is the key to the play’s success.

Opening the evening are Cath and Phil Tyler with their distinctive Anglo-American folk music, plaintive harmonies creating a powerful intensity both with instruments and unaccompanied.

A word for Newcastle’s Star and Shadow, a wondrous cinema/café performance venue of benevolent Bohemia run entirely by volunteers, a kindly slap in the face for our corporate society, set among the cultural renaissance area that is Ouseburn.

A short tour round Ouseburn Valley and its creative energy gladdens both heart and soul. Star and Shadow’s premises themselves are under threat. It’s vital they’re found a new home with as much idiosyncratic potential as the present one.